Automata Prototypes: Key West, FLORIDA

In January I attended the Peyton Evans Artist Residency at The Studios of Key West. This month-long residency was a welcome break from the midwinter cold of Baltimore, but also a time to recharge and challenge myself creatively. During this time, I set out to continue my exploration of kinetic sculpture and automata, working independently of digital and technological tools and experimenting with mechanical motion and expression through purely manual techniques.

Working without a dedicated woodshop or maker space, I limited myself to materials that were recycled or easily sourced from convenience and hardware stores, building automata prototypes out of cardboard, cut paper and wire. I am no stranger to working with these materials—I studied graphic design prior right at the advent of the computer age and was trained in manual pasteup techniques and production skills. While it was a rough start I was pleased to discover that muscle memory retained much of my skill with x-acto knives and rubber cement.

With these limitations and without reliance on technology or specialized equipment and materials I was able to work quickly, moving rapidly through iterations in a process more conducive to experimentation and more akin to playing. I had an almost limitless supply of sustainable material, and lots of time to fail and try again, and fail again if need be.

An abundance of time also allowed me to explore Key West and let my automata reflect what I found there. While the Keys are a place of natural beauty and eclectic cultural history, it has its complexities. On my day-to-day walks I’d see wild chickens, ibises, pelicans (and the occasional captive flamingo), but talking with locals, and visiting nature preserves encroached by golf-courses and condominiums told the story of a place that, while blessed with natural beauty is falling out of step with the creatures and resources that make it truly special.

The conversations and experiences I had during my time in Key West shaped these artworks as much as the materials and my hands did: from exuberance with the fantastically new and wonderful to the ambiguities accompanying familiarity, these machines trace the trajectory of a visitor’s relationship to a place when they visit long enough to notice the changes that come when they stay there long enough. While the space of a month is still not enough time to absorb nor convey the uniqueness of a place, I hope that the humor and vibrant colors of these pieces capture a bright passing fraction of it.

The Chic-o-mat

The first in a series of automata completed at the Peyton Evans Residency at the Studios of Key West, the Chic-o-mat salutes the native gypsy chickens that promenade around the streets, public places, and beaches of the Conch Republic.

Inspired by natural and built environment of this eclectic town, these automata draw from the native bird species I encountered during my visit. Using coffee cups, recycled cardboard, and wire, I created several iterations of the design, first sketching out the basic shapes and mechanism and then work towards a final finished off with collaged paper. (It should be noted that my chicken shapes grew better defined as I also set out to draw a chicken a day—a process that aided the design a great deal!

The Poor Spoonbill

In 2011, scientists and managers at the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary released the first comprehensive condition report of the region in its history. That assessment revealed a sobering truth: many of the sanctuary’s vital ecosystems—coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves—were in decline or degraded, and living resources such as fish and other wildlife were under persistent stress from human-driven pressures and environmental change.

Over more than a decade, residents, scientists, business owners, fishers, and conservation groups helped shape a proposal to help restore and prseerve native habitats while balancing the needs of local communities and the economy that depends on healthy marine resources. The report was finally released in 2025, and was vetoed by Gov. Ron DeSantis 46 days later.

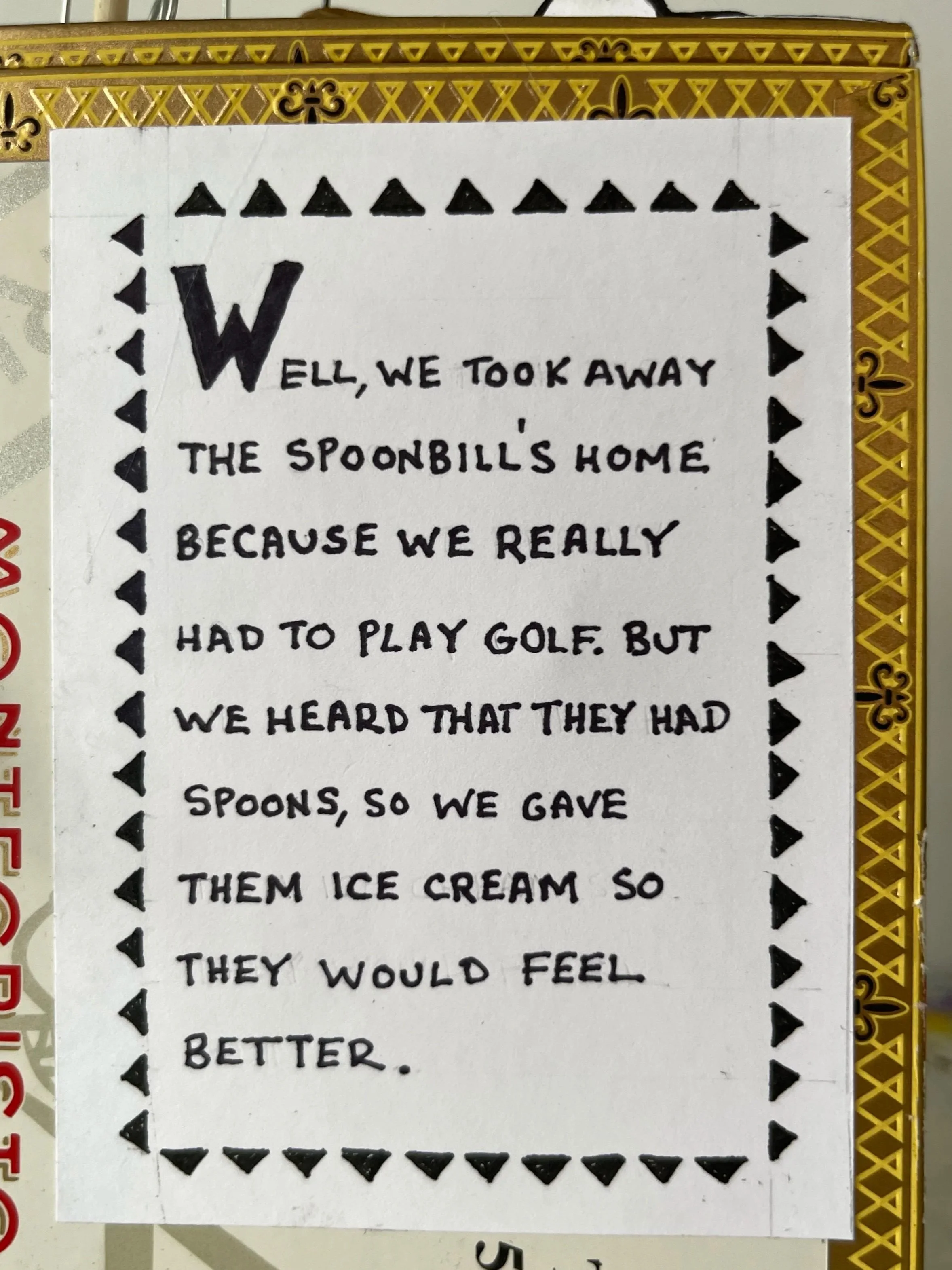

Failure to communicate over environmental issues falls hardest on the creatures that can’t advocate for themselves. Habitat loss is the leading cause of animal extinction in the Keys and all over the world, and the protections we put in place are often put the needs of commerce first. This imbalance leads to solutions that are ineffective, bordering on the absurd—a Rosate Spoonbill (a bird once commonplace in the Florida Bay) is no more capable of eating ice cream than speaking for itself.

The God of Wisdom is NOT AMUSED

I would not identify myself as a birder, but meeting wildlife in unexpected places is better than a celebrity sighting for me. While I was delighted by the feral chickens roaming the streets of Key West at will, seeing pelicans, frigate birds and other species native to the Keys was thrilling. Imagine my surprise when I met a White Ibis on a morning walk in the park.

With it’s bright eyes and mysterious smile, it’s no wonder the ancient Egyptians chose it’s African cousin the Sacred Ibis as the symbol of Thoth, the god of wisdom, learning, and magic. Thoth is often depicted as a human with a ibis’s head, recording the results of the judgement of souls in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

I imagine Thoth as a powerful but fussy deity—an immortal librarian type, perhaps. In this automata the god of wisdom watches us mortals nervously, shaking their head in dismay and upsetting their morning coffee.

This automata is an evolution of an ibis pull toy inspired by this encounter. You can find footage of the pull toy here.

Little gifts

I spent most of my time at the PEAR residency developing automata prototypes to bring back to my studio in Baltimore, where I could recreate them in stronger, more durable materials. I averaged one to two prototypes a week, and by the final week of my visit, I had run out of time to begin any larger works.

Still, I was in the midst of a creative surge—buoyed by the rare luxury of sustained experimentation and a renewed confidence in my hand-crafting skills. I wasn’t ready to stop. So I began working on smaller, more spontaneous models that were simpler representations of my experiences over the past month.

My time in Key West was a energetic and relaxing month, alternating between solid blocks of concentrated studio time and exploring. I met many people in the course of my explorations. Having the time to stop, talk and listen to people was almost as important as the discoveries I’d had in the studio.

In The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms this World, Lewis Hyde claims that art is a gift, not a commodity: artistic inspiration is a creative act of generosity, and that creative work loses meaning if reduced purely to commodity. Honoring this idea is something that’s deeply important to me. The small mini-matas (as I’d dubbed them) were designed to be left behind, designed to be simple gestures of thanks to the people who shaped this extraordinary experience.